On 19 August 1509, Emperor Maximilian signed the infamous Padua Mandate, thereby authorizing confiscation of Jewish books in the Holy Roman Empire on the grounds that they contained elements that were heretical, blasphemous and libelous. The emperor also claimed that the books "turn you away from our Christian faith."

Johannes Pfefferkorn immediately launched the ground war, the actual implementation of the mandate, in Frankfurt am Main, home to one of the most vibrant Jewish communities of the day. The anti-Jewish forces hoped that success in Frankfurt would build unstoppable momentum; that the first battle would decide the entire war.

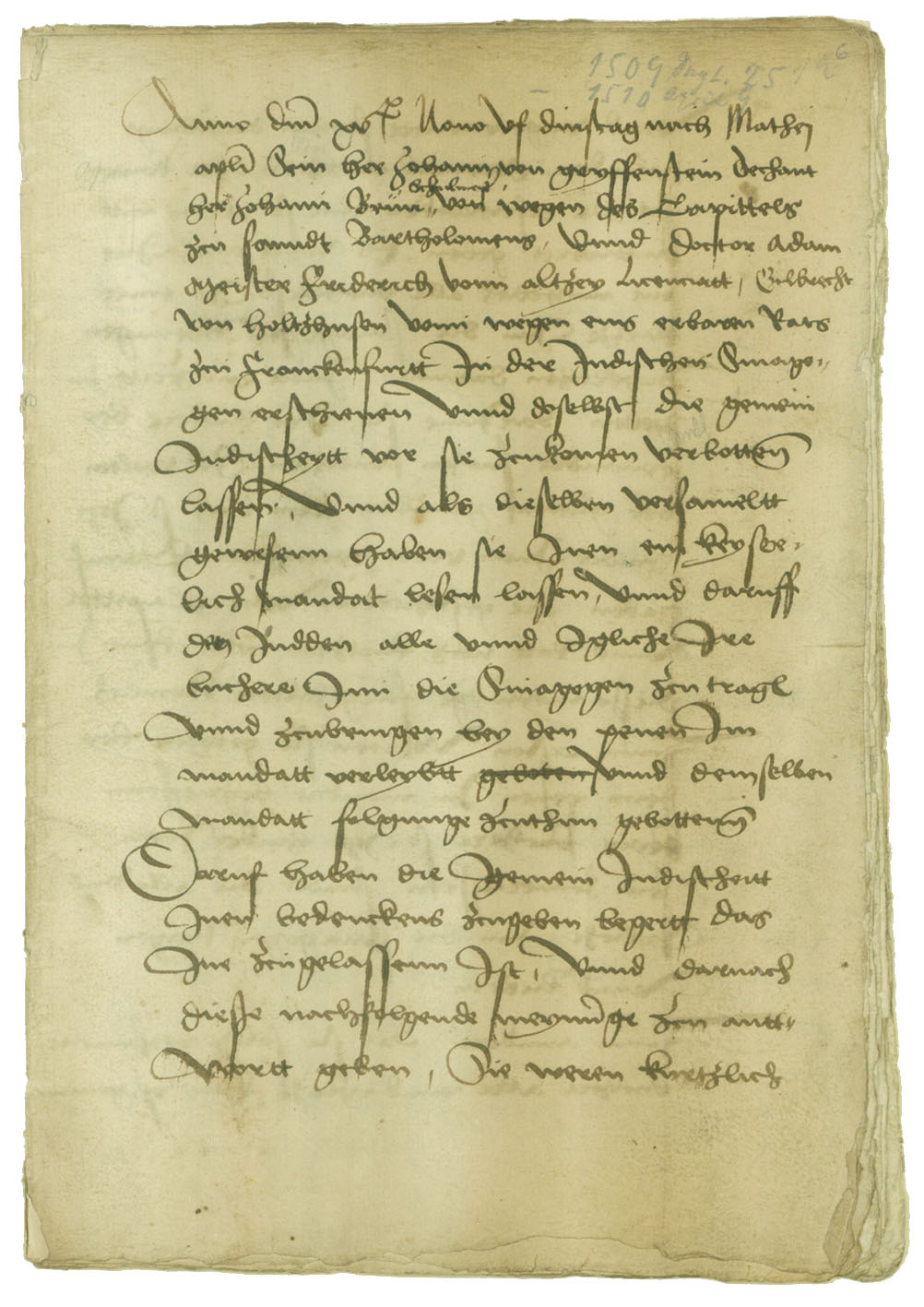

Nonetheless, it initially proved difficult to build momentum in Frankfurt. As soon as the new policy was announced in the Frankfurt synagogue on 25 September 1509, the Jewish Community and the City Council of Frankfurt undertook every possible effort to undermine or delay implementation. On 28 September 1509, Pfefferkorn was able to confiscate all books in the synagogue library except the Bible, but the removal of all private books in Jewish hands was blocked by Uriel of Gemmingen, Archbishop of Mainz, in response to a petition from the community.

That set the stage for a showdown between Jonathan Kostheim, a leading member of the Frankfurt Jewish Community, and Johannes Pfefferkorn at the court of Maximilian, then in northern Italy. Despite Kostheim's determined efforts, the confrontation was a resounding success for the anti-Jewish campaign. Maximilian reissued the confiscation order in the Roveredo Mandate of 10 November 1509, now authorizing the archbishop of Mainz to supervise implementation of the policy.

The anti-Jewish forces, now spearheaded by Pfefferkorn and the Mainz theology professor Hermann Ortlieb, decided to resume the confiscations in Rhineland communities other than Frankfurt. Beginning in December 1509, they swiftly seized all Jewish books in several important communities, first in Wurms, still a major center of Jewish learning, and then in Mainz, Bingen, Lorch, Lahnstein, and Deutz.

Although Pfefferkorn and Ortlieb had not returned to attack the Frankfurt Jews, the City Council and the Jewish Community of Frankfurt continued to challenge the legality of the mandate. In January 1510, the City Council began sending instructions to its emissary at the imperial diet in Augsburg to aid the Jewish community in its efforts to quash the mandate. This culminated in the city's demand to Maximilian on 16 March 1510 that the books seized from the synagogue library be returned to the community.

Johannes Pfefferkorn was also present at the Diet of Augsburg, actively campaigning for the policy. He issued an inflammatory pamphlet, In Praise and Honor of Emperor Maximilian (Augsburg, February 1510), to bolster support for the Roveredo Mandate.

In a dramatic move, Pfefferkorn and Professor Ortlieb left Augsburg for Frankfurt, with the intention of implementing the mandate without further authorization or clarification from Maximilian or the estates of the empire. They appeared in Frankfurt on 22 March, insisting on their right to proceed. In consideration of the coming Easter holiday, the Council requested a delay until 10 April for surrendering the books. On about 3 April, the Council sent a complex, but powerfully argued petition to its emissary in Augsburg for submission to Maximilian. It insisted that the confiscation decree was illegal because civil and ecclesiastical law granted the Jews property rights as well as the freedom to practice their religion.

Since the emperor did not respond to the city's petitions, Pfefferkorn and Ortlieb were able to proceed on 10-11 April 1510 with a complete confiscation of Jewish books in Frankfurt with the exception of the Hebrew Bible and books owned by non-Frankfurt residents. An inventory of 13 April indicates that nearly 1500 Jewish books were confiscated.

Nonetheless, the Frankfurt Jews did not concede defeat. On 23 May 1510, in a stunning turnaround, the emperor abruptly revoked authority for the confiscation and ordered the return of all Jewish books. The concession was granted in consideration of the willingness of Jewish creditors to renegotiate a loan to Duke Erich of Braunschweig, an important military ally of the emperor. The Jews of Frankfurt received their books on 7 June 1510, but with the stipulation that the books remain in Frankfurt pending the emperor's final formulation of a policy.

The agreement, thus, was only a temporary suspension of the policy. On 6 July, the emperor issued the Füssen Mandate, which authorized a legal and theological assessment of the confiscation policy. This step was probably taken in part as a response to the legal challenges raised by the Frankfurt City Council. With academic endorsements in place, the emperor would again be able to authorize seizure of Jewish books.

This development looked so ominous that the City Council of Frankfurt warned the Jewish Community that confiscations were about to resume.