The worlds of academia and anti-Jewish agitation were not separate realms in medieval and early modern Europe. Soon after the publication of his Hebrew grammar, the father of Christian Hebrew studies found himself at the center of the anti-Jewish maelstrom, when Emperor Maximilian declared a moratorium on the book confiscation in a mandate of 23 May 1510. In no way connected to Reuchlin’s intervention, this initial suspension of the campaign resulted from tough negotiations between the emperor, the archbishop of Mainz, the city of Frankfurt, and the Jewish community of Frankfurt.³ Nonetheless, as a prelude to resuming the pogrom, the emperor issued a new mandate on 6 July 1510 that required legal and theological evaluations of the confiscation policy from four universities and three individual scholars, including Reuchlin. While all the other experts submitted enthusiastic endorsements for implementing the new policy, to everyone’s astonishment, Reuchlin argued against Maximilian’s tactic, forcefully contending that the book confiscation did not accord with imperial law and was not justified on religious or theological grounds. He carefully elaborated this defense in an extensive legal analysis he sent the emperor in October 1510 and, then, published in 1511, under extreme provocation, as the centerpiece of Eye Glasses. Although his conclusion stood alone among the seven evaluations, Reuchlin’s defense was so powerfully argued that it effectively stymied the new and dangerously potent method of persecution. As far as we know, all the books were returned to their Jewish owners and, despite determined efforts, the strategy was never again attempted in early modern Germany.

Nonetheless, Eye Glasses plunged Christian Europe into a wrenching controversy. The acrimony originated in the massive efforts undertaken to refute Reuchlin’s defense in order to secure imperial permission to restart the campaign against Jewish culture. Although a confidential brief, once Reuchlin’s recommendation had been submitted, Pfefferkorn, Hoogstraeten, and the archbishop of Mainz had access to it. All interested parties immediately realized that because of Reuchlin’s stature and the comprehensiveness of his analysis, his recommendation posed a substantial impediment to any resumption of the confiscations. Apparently even before the report was forwarded to the emperor, the archbishop of Mainz arranged for a commission, led by the Carthusian Gregor Reisch, to condemn Reuchlin’s views as "scandalous." For his part, Johannes Pfefferkorn reached for his customary weapons—pen and paper—and attempted to obliterate Reuchlin’s legal argument in Magnifying Glass, a scorching invective that was released for distribution at the Frankfurt Book Fair in spring 1511. As indicated on the title page, Magnifying Glass attacked both the Jews and "several Christians" who defended them. In fact, this was the book that initiated the Reuchlin Affair, for it was only in response to Magnifying Glass that Reuchlin decided to publish his defense of Jewish books for all the world to read.

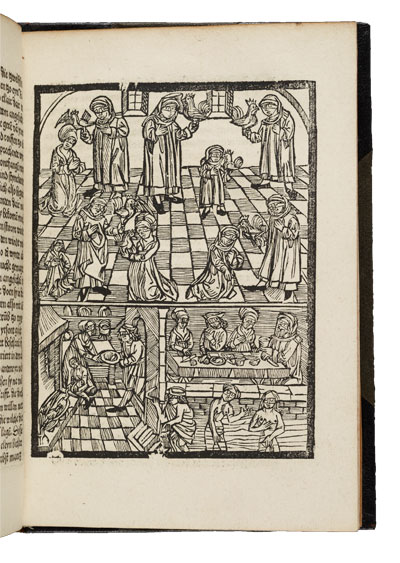

Prefiguring the inquisition’s heresy charges, Pfefferkorn assailed the argumentation of Reuchlin’s defense with an impressive apparatus of legal and ecclesiastical authorities. The bulk of Pfefferkorn’s poisonous rhetoric, however, is not directed at Reuchlin, for, as Pfefferkorn said in 1512, "I did not publish [Magnifying Glass] against him but against the Jews." In this new diatribe against Judaism, he portrays contemporary Jews not only as blasphemers and heretics, but also as murderous enemies of Christians. Most dangerously, Pfefferkorn conjures up the deadly specter of blood libel and host desecration cases. The pamphlet cites four recent cases of host desecration, along with breaking news about a major incident, the Berlin host desecration travesty of 1510. The Berlin case resulted in the execution of thirty-eight Jewish victims as well as the banishment of all Jews from Brandenburg. Pfefferkorn’s endorsement of these terrible judicial hoaxes is unusual—other prominent converts who became anti-Jewish campaigners did not malign their former brethren with such patently false—and deadly—accusations. Many Christian authorities knew that these witch hunts were illegitimate. Popes and emperors routinely forbade their prosecution—often to little avail with local authorities. The Brandenburg convictions would even be rescinded in 1539 and Jews would be able to resettle there. But Pfefferkorn chose to exploit these myths in order to dramatize his contention that Jews are dangerous and nefarious enemies of Christianity and to denounce Reuchlin for claiming that the Jews could be a benign presence in Christian society.

Moreover, since the campaign to destroy Jewish writings remained his goal, Pfefferkorn meticulously repeated the specific allegation used in his previous tracts. In particular, he offered a direct rebuttal to Reuchlin’s philological defense of Jewish prayers, insisting, on the strength of further quotations from Hebrew writings, that Jews blaspheme Christianity. Now he presents twenty articles against the Talmud, contending that his sampling of Talmudic perversions of Judaism was sufficient to warrant eradication of the book. Magnifying Glass also reveals the close collaboration between Pfefferkorn and the Cologne theologians. The tract was dedicated to Professor Arnold van Tongern and deploys the same arguments the faculty would make later in their attacks on Reuchlin. When citing canon law against Reuchlin, Pfefferkorn explicitly says that theologians provided him with all the references.

Inquisitor Jacob Hoogstraeten and the University of Cologne soon brought forward formal charges of heresy, alleging on the basis of forty-three statements that Reuchlin’s Eye Glasses was "impermissibly favorable to Jews." In 1512, these charges were published under the authorship of Professor Tongern as part of the effort to discredit Reuchlin, and, while the heresy trial was wending its way through ecclesiastical courts, the University of Cologne also raised the stakes for academia by securing formal condemnations of Reuchlin’s Eye Glasses from other major theological faculties across Europe, including Paris and Louvain.

By 1513, the controversy was being discussed everywhere in Europe in part because it implicated the champion of the new Renaissance humanist methodology for biblical studies and in part because eradication of European Jewry was then such a burning issue. Many authorities tried to influence the outcome of the case, one way or the other—the emperor (Maximilian I), the future emperor (Charles V), the current pope (Leo X), a future pope (Adrian VI), two kings of France (Louis XII and Francis I), other princes, secular and ecclesiastical, some fifty cities in the Holy Roman Empire, university faculties, professors and scholars all over the Continent and even in England. The resulting trials, which persisted until Pope Leo X handed down a final ruling in 1520, reveal some of the most unstable fault lines in European intellectual culture, some of which would shift violently as the century progressed. Reuchlin’s writings and the chain reaction they touched off mark the first time in European history that some Christians undertook an academic study of Judaism and its history.

Initially, Reuchlin’s opponents were motivated by their resolve to annihilate Judaism but soon some began to express additional concerns about where Renaissance humanism might lead—not only to increased toleration of Jews but also to new approaches to Christian theology, and perhaps even to a different conceptualization of Christianity. On the other hand, Reuchlin’s path-breaking research in Hebrew elicited admiration from many enthusiasts of the humanist movement. The ability to associate his position on Jewish writings with humanist scholarship, specifically to the process of Christianity returning to its Bible in the original languages, immediately mustered an elite cohort of supporters for his cause. This configuration not only created a public forum for debate on the proper Christian attitude toward Judaism but also led to a major confrontation between scholasticism and humanism. Together, these two conflicts made up the Reuchlin Affair.

3. See David H. Price, Johannes Reuchlin and the Campaign to Destroy Jewish Books (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 113-37.