In Eye Glasses, Reuchlin based much of his argument on civil law, especially on his contention that Jews residing in the empire were not serfs or slaves but rather fellow citizens ("concives"): "We and they are fellow citizens of one and the same Roman Empire."4 Although he did not intend this as an assertion that, over all, Christians and Jews had equal legal rights, it did mean that, as fellow citizens, Jews were protected from state seizure of their property.5

Reuchlin’s "concives" argument immediately encountered a torrent of opposition. Many theologians, such as Duns Scotus, had held the view that Jews fell under the category of slaves and were therefore excluded from many basic rights of citizens. The jurist Ulrich Zasius, perhaps the most influential German legal scholar of the early sixteenth century, had even used the concept of Jewish servitude as a basis for arguing, in a notorious case, that Jewish children could be taken legally from their parents by force and baptized. Reuchlin vehemently rejected the legality of coercive baptism in Eye Glasses and elsewhere.

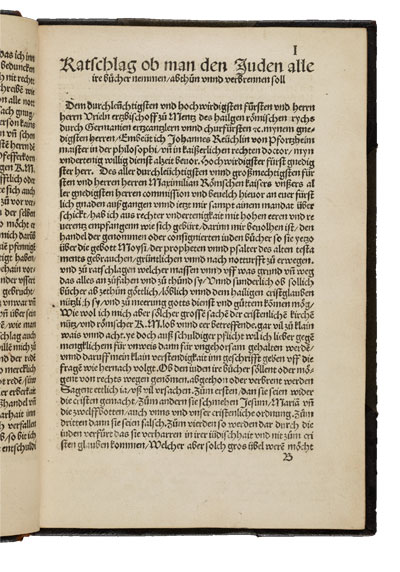

But even on these issues, it is important to observe Reuchlin’s deeper reliance on ecclesiastical law codes. Referring specifically to passages in the Decretales of Pope Gregory IX, Reuchlin wrote, "Therefore, we are ordered in ecclesiastical law, in Sicut Judaeis, not to take their belongings from the Jews, whether money or something of monetary value."6 Indeed, basic property rights had been enshrined in the foundational medieval law governing Christian-Jewish relations: the Sicut Judaeis, often called the Constitution for the Jews, a papal bull first issued in the 1120s but harking back to policies formulated by Pope Gregory the Great (590-604). When he composed the defense in 1510, Reuchlin had not yet read Hoogstraeten’s evaluation and was unaware of his plan to convene a new inquisition against Jewish books in the empire. According to his own account, Reuchlin was motivated by a desire to stop Maximilian, not the church, from an illegal and destructive blunder. Apparently, however, Reuchlin could already envision the campaign as a matter headed for ecclesiastical adjudication. Moreover, the specific questions in Maximilian’s request for evaluation—such as, would destruction of the Jewish books benefit Christianity?—suggested that the ultimate legal authority would be ecclesiastical. Consequently, Reuchlin’s analysis often sounds like a preemptive defense against putative inquisitional charges in addition to being a legal memorandum prepared for the Holy Roman emperor.

Even if under both civil and ecclesiastical law the Jews enjoyed the right to own such things as religious books, those books would still be subject to seizure and destruction by the state, if they were heretical, blasphemous, or libelous. Reuchlin addressed this as the most serious legal question. And, to his mind, the answer hinged on an accurate analysis of the evidence—the Jewish books themselves.

In the end, Reuchlin’s assessment of Jewish literature was a devastating blow to the campaign to destroy Jewish books. This was the prime reason that so many authorities attacked him with such fury and resolve. After compressing a comprehensive review of Jewish writings to pamphlet size, Reuchlin authoritatively pronounced Jewish books innocent of all charges of blasphemy and heresy, with the exception of two minor books that, according to Reuchlin, were taboo among Jews anyway. Moreover, Reuchlin pursued the secondary goal of constructing a theological history in which Christianity acknowledges benefits from Jewish writings.

4. Johannes Reuchlin, Augenspiegel (1511), in Reuchlin, Sämtliche Werke, ed. Widu-Wolfgang Ehlers, Hans-Gert Roloff, and Peter Schäfer (Stuttgart-Bad Cannstadt, Frohmann-Holzboog, 1996-), 4/1:35, ll. 5-6.

5. Reuchlin, Augenspiegel (1511), in Sämtliche Werke 4/1:28, ll. 7-8.

6. Reuchlin, Augenspiegel (1511), in Sämtliche Werke 4/1:62, ll. 13-15.