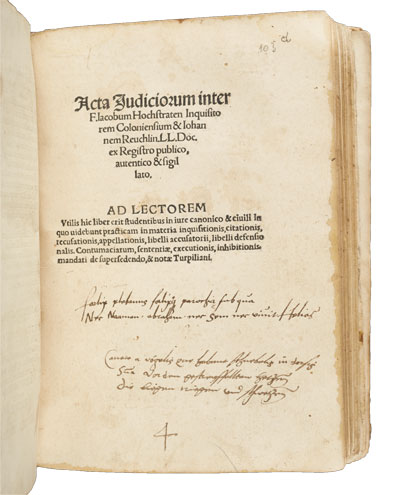

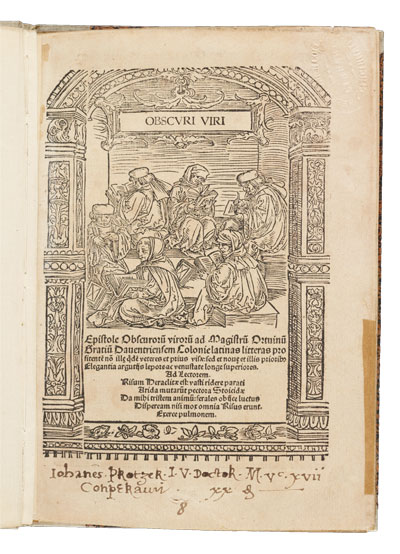

The trials of Reuchlin elicited many defenses and attacks and also resulted in two preliminary verdicts. A 1514 episcopal court in Speyer pronounced Reuchlin innocent of all charges of having "favored" Jews and, in an unprecedented ruling, assessed the papal inquisition (in the person of Jacob Hoogstraeten) for the defendant’s court costs. An appeals court at the Roman Curia reached a similar verdict in 1516. Nonetheless, on 23 June 1520, just eight days after signing the first thundering condemnation of Martin Luther, Leo X issued a verdict against Reuchlin. In the aftermath of Luther’s Ninety-five Theses (1517), the Vatican was simply no longer in a position to allow challenges against inquisitional forces in Germany to go forward. Indeed, in April 1521, at the beginning of the Diet of Worms (where Luther would be condemned by the estates of the empire), Pfefferkorn wrote: "Yes, Reuchlin, if the Pope had done this to you eight years ago, Martin Luther and your disciples … would not have dared to wish or contemplate what they are now publicly pursuing to the detriment of the Christian faith. Of all this, you alone are the spark and the enabler, to drive the holy church into error and superstition."15 Reuchlin, however, ultimately repudiated Luther’s movement and remained a Catholic until his death on 30 June 1522.

Despite the papal condemnation, a permanent foundation had been laid for Christian Hebrew studies. We can assume that Reuchlin was not the only Christian of his generation who admired his Jewish books and acquaintances, but he was the first to represent Jewish theology and Jews themselves with a measure of benevolence, sometimes even unqualified admiration, in public discourse. When it came to a few Jewish thinkers, his opponents’ accusations, though bitterly formulated, that he valued Jewish authorities more than the doctors of the church were not entirely specious. Major Jewish scholars such as David Kimhi, Rashi, Joseph Gikatilla, and, above all, Moses Maimonides impressed him at a very deep level. It is not astonishing that he acknowledged the importance of Talmudic and medieval Jewish scholarship—even Luther consulted Jewish scholarship for his Old Testament exegesis—but it is striking that he so openly registered agreement with the wisdom and piety of the Jewish authors he studied. Yet, once again, Reuchlin would have considered his attitude nothing more (and nothing less) than a reasonable and just academic judgment of the works themselves.

Reuchlin would not be the only Christian scholar to defend Jews and Judaism against injustice. One of his students, Andreas Osiander, the leading reformer of Nuremberg, diligently continued his studies of Hebrew and Jewish writings as part of his ministry and, in 1529, emulated his teacher by composing an academic refutation of the pernicious accusations that Jews used the blood of murdered Christians in their rituals. But Osiander’s theological rejection of the blood libel innuendo, grounded in knowledge of Jewish practices, provoked an unusually strident objection from another of Reuchlin’s students, the Catholic theologian Johannes Eck. In this clash between two Reuchlin followers, we can plainly see that Christian Hebraists in the aftermath of Reuchlin would not by any means develop a uniformly favorable attitude toward Judaism, even if by the beginning of the seventeenth century a detectable "philosemitism" existed among some Christian scholars. Several of Reuchlin’s supporters, including a few of the most influential theologians on all sides of the confessional divides, would advocate using political force and, as in the case of Luther, violence to end the practice of Judaism in Germany. Like Pfefferkorn and Hoogstraeten, they assailed Judaism not only as a defective faith but also as a menace to Christian society that had to be eliminated by political means, no matter how inhumane.

Although a "miracle within a miracle" to a Renaissance rabbi, Johannes Reuchlin can be understood in historical terms as the beginning of a significant development: Christians acquiring accurate knowledge of Judaism and its history. Reuchlin was arguably the first Christian to read ancient and medieval Jewish texts with primarily scholarly rather than polemical interests. Over time, Jewish books and Jewish teachers equipped him with the knowledge, and ultimately inspired him with the conviction, to explain and defend the integrity of the Jewish tradition to his Christian world.

15. Johannes Pfefferkorn, Ajn mitleydliche claeg (Cologne: Servas Kruffter, 1521), fol. H2r.