While this curtain was falling on European Jewry, act one, scene one of a new Christian-Jewish drama began. A tiny number of Christian scholars were starting to cultivate contacts with learned Jews for a rather different purpose—they were seeking Hebrew and Jewish scholarship, hoping to acquire new methods for theological education and research. Ultimately they would succeed, for the embrace of Hebrew in the Renaissance would invigorate Christian scholarship and lay a permanent foundation for the modern study of the Bible. This started in the 1480s, when suddenly the Renaissance ideal of returning "to the sources" of ancient culture was applied to Christianity, introducing the biblical methodology that would include the recovery of Hebrew Scriptures and would soon undergird the Protestant reform movements. Despite explicit repudiations of Judaism, this development amounted to implicit acknowledgment by Christians that Jewish tradition and learning possessed value for them. A few Christians, virtually for the first time in the history of their religion, expressed enthusiasm for Jewish studies.

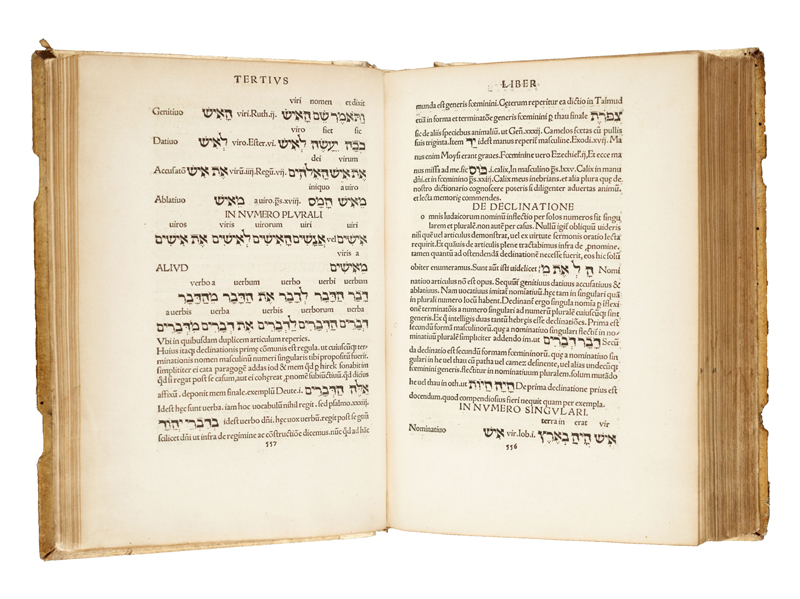

By 1506, a watershed in the history of Christian scholarship, Johannes Reuchlin had learned enough from leading Jewish scholars to publish the first Hebrew grammar and dictionary written for Christians, his Rudiments of Hebrew. No less an authority than the modern Jewish historian Gershom Scholem aptly described him as "the first scholar of Judaism, its language and its world, especially the Cabala … the man who, nearly five centuries ago, brought to life the discipline of Jewish studies in Europe."²

Reuchlin’s grammar was the first step in a sweeping movement. In the 1510s and 1520s, scholars in the leading centers of humanist culture—Florence, Venice, and, above all, Rome—promoted Hebrew scholarship as one of the great promises for a renewal of Christianity. In the 1520s, the inchoate Protestant movement decisively embraced Hebrew philology, and, by the 1530s, Hebrew studies were firmly established at universities throughout western Europe.

2. Gershom Scholem, Die Erforschung der Kabbala von Reuchlin bis zur Gegenwart (Pforzheim: Im Selbstverlag der Stadt, 1969), 7.