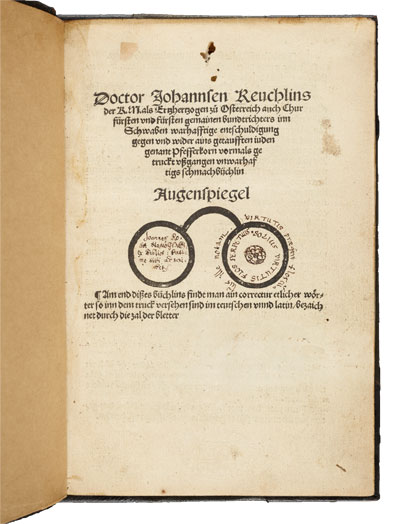

A little over five hundred years ago, in September 1511, a compact book entitled Eye Glasses appeared at the international Frankfurt Book Fair and immediately polarized Europe. The author was the universally respected scholar and jurist Johannes Reuchlin, but the subject of Eye Glasses was not destined to find universal acclaim: it was a comprehensive legal and theological defense of Jewish writings. The context of the publication heightened the controversy, for Reuchlin wrote the defense in order to thwart a dangerous persecution that was aiming to destroy every Jewish book in the Holy Roman Empire. After the ensuing intellectual and political storms had passed, Josel of Rosheim, the most influential Jewish leader of Renaissance Germany, described the historic intervention as a "miracle within a miracle,"¹ remembering with unabated amazement that a Christian scholar had defended the Jews and, more astonishing, that he had prevailed.

The unprecedented defense of Judaism was a response to an unprecedented attack that began in earnest in 1509. Until then, campaigns against German Jews, though numerous and often effective, had been limited to individual territories within the empire. The goal of the 1509 persecution was to weaken and break the surviving Jewish communities in one comprehensive effort by confiscating and destroying every Jewish book except the Hebrew Bible, thereby making it impossible to practice the religion properly. This aggressive strategy, carefully formulated to be compatible with imperial law, was initially spearheaded by Johannes Pfefferkorn, a recent convert to Christianity who had been agitating against Jewish communities in Germany since 1505. By the end of 1509, the confiscation campaign was being supported by the emperor, the archbishop of Mainz, the University of Mainz, the University of Cologne, the powerful Dominican convent in Cologne, the Observant Franciscan Order, and the papal Inquisitor Jacob Hoogstraeten.

Initially, the most potent weapon against the Jews was the printing press. Before Emperor Maximilian authorized destruction of Jewish books, Pfefferkorn and the faculty of theology at Cologne published a series of stridently anti-Jewish tracts: Mirror of the Jews (1507), Confession of the Jews (1508), How the Blind Jews Observe Their Easter (1509), and The Enemy of the Jews (1509), all of which appeared simultaneously in both German and Latin editions. Counting the German originals and the Latin translations, these books went through an astounding twenty-one editions within three years. Although ostensibly published as missionary tracts, the inflammatory pamphlets were designed to stoke the fires of Christian anti-Semitism. They assailed contemporary Judaism as a heresy (i.e., as being a perversion of biblical Judaism) that must be rooted out, and they depicted Jewish customs and prayers as intolerable blasphemies against God. Moreover, the pamphlets insisted that Jewish moneylenders were engaged in a pervasive effort to destroy Christian society. These pamphlets rapidly built the political momentum that, in August 1509, secured the decisive step from Maximilian: a mandate to confiscate and destroy the offending Jewish books.

Implementation of the new policy began in September 1509 in Frankfurt am Main, home to one of the three most prominent Jewish communities in Germany (the other two being Worms and Regensburg). Despite strong resistance from Jewish leaders, a complete confiscation in Frankfurt was carried out by April 1510, and other Rhineland communities, including Worms, also suffered confiscations in 1509 and 1510.

This action occurred at a time when all of Europe was contemplating the end of Judaism. After the expulsion of the world’s largest Jewish community from Spain in 1492 and the forced Portuguese conversion of 1497, European Judaism was tottering at the edge of the abyss. Jews had long since disappeared from England (expulsion 1290) and France (expulsion from crown territories, 1394). Expulsions had also been mandated in many individual territories across the Holy Roman Empire—Vienna (1420/21), Cologne (1424), Bavaria (1442/50), Würzburg (1453), Passau (1478), Mecklenburg (1492), Magdeburg (1493), Württemberg (1498), Nuremberg (1498–99), Ulm (1499), and Brandenburg (1510), to name but a few. During the second half of the fifteenth century, the area open to Jewish residency contracted with every passing year. Various jurisdictions in Italy, the only major homeland to western European Jewry outside of the empire in 1509, were following suit. As a result of the spread of Spanish rule, Jews were banished from Sicily in 1492 and from the Kingdom of Naples through a series of expulsions, with the strongest intensity during 1511–14, that concluded in 1541. This moment in history, which instigated the early modern exodus to Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire, marks the nadir of Jewish life in western and central Europe prior to the Holocaust.

1. See Ludwig Feilchenfeld, Rabbi Josel von Rosheim (Strassburg: Heitz, 1898), 22. Quote is according to Isidor Kracauer, "Rabbi Joselmann de Rosheim," Revue des Etudes Juives 16 (1885): 88 (section 5). See also Chava Fraenkel-Goldschmidt, The Historical Writings of Joseph of Rosheim (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 312.